Last Week, I posted a

"top 10" list. Since then, I've been thinking about doing another one that was a bit more specific to this blog. Here is a list of my top 10 favorite ecosystems in the world. I have actually visited all of these, except one, as will become apparent.

1. Tallgrass Prairie

Bluff Spring Fen

Any list of my favorite ecosystems would have to start with this one, if only because I have now spent over half of my life studying, managing, and restoring examples of this ecosystem.

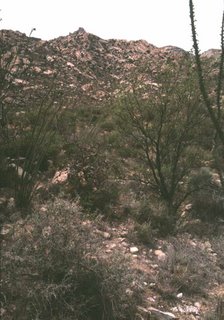

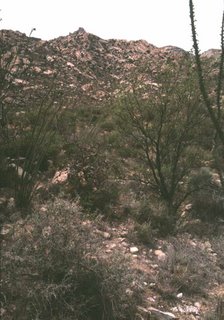

2. Sonoran Desert Scrub

Below Kitt Peak, ArizonaThe first time I visited the Sonoran Desert was spring of 1988. I went for a hike in the west unit of Saguaro National Park (then still Saguaro National Monument). The spring flowers were in full bloom, but what struck me most was the larger vegetation. Saguaro cactus is really playing the role of a tree in this ecosystem. There are other trees, too- vase shaped ocotillos, gnarly desert hackberries, spiny mesquite trees, twiggy palo verdes. I began thinking of the place as the enchanted forest. It’s a desert. Yet in its own way it’s also a forest- but the trees all look somehow like they should be growing on the bottom of the ocean. It’s now nearly 20 years later, and I still feel the same sense of enchantment every time I visit.

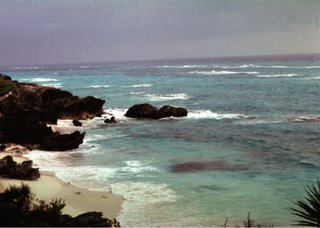

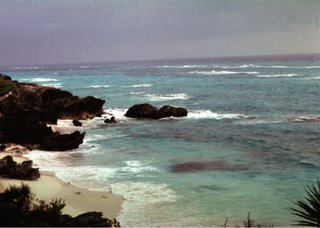

3. Bermuda Cedar Forest

Top: Bermuda Coast Bottom: Remnant Cedar ForestSadly, some of my favorite ecosystems have virtually vanished from the planet. The island of Bermuda was once clothed with a dense forest dominated by Bermuda Cedar, a native palmetto, and Bermuda Olivewood. All of these trees are endemic to Bermuda, that is, they grow naturally nowhere else in the world. All three are now threatened with extinction. As with so many islands, the native ecosystem of Bermuda has been ravaged by development and the changes brought about by the introduction of non-native species to the islands. Ecologist David Wingate has done a masterful job of restoring an example of this ecosystem on Nonesuch Island, a tiny islet off shore from the main island. In addition, Wingate has been instrumental in bringing a bird called the Bermuda Petrel, or Cahow, back from the brink of extinction. Wingate estimates that for 200 years prior to recovery activities focused on the Cahow, there were never more than 15 breeding pairs alive at any time. The survival of the species along such a tenuous thread of existence is the stuff of near miracles.

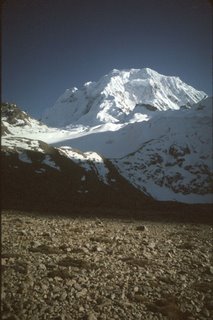

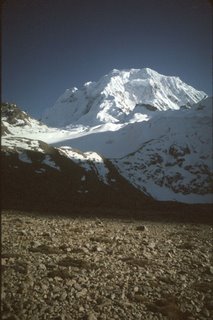

4. Puna

At 15,000' below Salkantay, PeruThis is the one that you are least likely to guess where or what it is from the name of the ecosystem. Puna is a high elevation grass and scrubland found in Peru and adjoining countries. In 1989, my partner and I spent a week backpacking in the Cordillera Vilcabamba north of Cuzco. It’s always a bit disorienting for me when I do something like this, as I’m used to being familiar with a good fraction of the plant species that I’m seeing while out and about. Our travels took us past tropical mountain glaciers, over a 16,000 ft mountain pass, and through scenery as beautiful as anything I’ve ever encountered elsewhere. One valley that we descended into was home to plants that were close relatives of familiar prairie plants growing there. It felt sort of like home except that dotted among the tick trefoils and geums were beautiful yellow oncidium orchids in full bloom.

5. Fan Palm Oasis

Southwest Grove, Anza Borrego State ParkIn the deserts of southern California, there are places where faulting forces groundwater up to the surface. Here the only species of palm tree native to the western United States takes hold. Its amazing to sit in the shade of the palm trees looking out at the harsh desert light outside of the oasis. The air is much cooler, there is lots of bird activity up in the palm fronds, and the entire oasis buzzes. The sound is from hundreds of bees collecting water from the damp mud at the edge of the pools that are found in many of the palm groves.

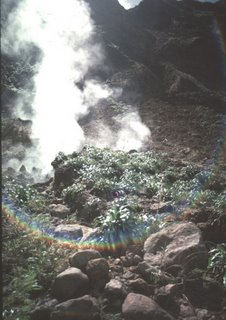

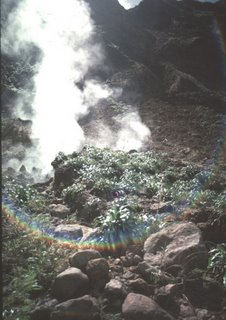

6. Windward Islands Rain Forest

Top: Dominica Bottom: Vegetation around fumeroleThe windward islands form the boundary between the Caribbean Sea and Atlantic Ocean. They are steep sided volcanic mountains. Dominca is the most unspoiled of the lot and covered with dense rain forest. At higher elevations there are fumeroles, hot springs, and even a boiling lake. Two rare species of endemic parrots fly in the rain forests. In one area, there is a ravine about 30 feet deep and about three feet wide. Dominica offers a glimpse of what the islands of the region looked like before Columbus.

7. Florida Pine Rocklands

Big Pine KeyThe Florida rocklands are an ecosystem that I have come to know only recently. It is now confined to portions of the Everglades, and to Big and Little Pine Keys about three quarters of the way from Miami to Key West. The soil is very thin over a layer of fossilized coral reef that pokes through the soil here and there. There are sinkholes scattered about where rare ferns and orchids can sometimes be found. There is a strong Caribbean influence to the vegetation. The rocklands of the Everglades are always enjoyable to visit because we encounter coontie, a native Floridian species of cycad that is the host plant of a rare butterfly called the Atala. Cycads are a passion of my partner’s so we both enjoy finding them. Contributing to my enjoyment of this ecosystem is the fact that we usually visit on our annual vacation to the Florida Keys, where we get to spend time with some good friends. This year instead of going to the Keys we will visit Costa Rica, where we will encounter:

8. Central American Cloud Forest

Volcán Poas, Costa RicaThis is a high elevation tropical forest. It’s typical of some of the Central American volcanoes. I am most familiar with it from Poas Volcano in Costa Rica. Many people will be surprised that I have chosen a butterfly-poor habitat as one of my favorite tropical ecosystems, but it’s a beautiful one. The forest is somewhat stunted and twisted by the mountain winds. The branches of the trees are covered with a denser growth of epiphytic orchids, ferns, and bromeliads than I have seen anyplace else in the world. It’s often misty, as one is engulfed in the clouds that give this ecosystem its name, and this contributes to the relatively poor abundance of butterflies. But there are hummingbirds everywhere, and it’s a real treat to see them flitting among the bromeliads, taking nectar from the bright red flower spikes.

9. Sierra Nevada Alpine Zone

Top: The High Sierra Bottom: Behr's SulphurThis is another sparse and austere ecosystem. The dominant feature is very white granite everywhere, but there’s lots of life, too. In the zone ranging from near to above treeline, beautiful alpine meadows grow interspersed with groves of stunted conifers. The meadows are often filled with dozens of species of colorful wildflowers, including lupines, gentians and monkey flowers. Despite the harsh climate, this is an area rich in butterflies. One of my favorites is Behr’s sulphur. It lives in the high California Sierras and nowhere else in the world. It’s a member of the large genus Colias, which includes many of the little yellow butterflies common throughout temperate regions. Behr’s sulphur is the only member of the genus that is predominantly green.

10. Hydrothermal Sea Vent

Black Smoker and Giant Tube WormsThis is the coolest ecosystem that I will never have the opportunity to visit. Vent communities are located in the perpetual darkness of the ocean floor, in geologically active regions. Underwater geysers called black (or white) smokers spew ferociously hot water filled with compounds in a reduced chemical state. Not the sort of things that we commonly consider to be nutrients, the power the bacteria that form the base of the food chain here. Unlike more familiar ecosystems, these nutrients enter the food chain from the Earth’s mantle, rather than from the sun via photosynthesis. Organisms that live here must cope with the extreme pressures of the ocean depths, total darkness, and temperatures that can range from above the boiling point of water (the pressure keeps it liquid) to icy cold. Despite these challenges, far from being species-poor, these are very rich ecosystems. Their inhabitants can include crabs, clams, mussels, giant tubeworms that can be over six feet ling and have no mouths, and even fish. Because of their great remoteness in the ocean depths, these communities remained unknown until the 1970s.

Labels: Ecosystems